Who knows where it started. With Fox Mulder and Dana Scully, maybe? Regardless, the cult of secrecy went mainstream in the “watch-what-[you]-say,” “secret-even-in-success” days following 9-11.

Who knows where it started. With Fox Mulder and Dana Scully, maybe? Regardless, the cult of secrecy went mainstream in the “watch-what-[you]-say,” “secret-even-in-success” days following 9-11.

The cult has, unfortunately, endured.

For a while, there was hope. It seemed the colossal disasters enabled by obsessive secrecy, such as the “Curveball” fiasco, could inspire a backlash in favor of openness and transparency.

Recent events, however, suggest that the cult of secrecy has grown stronger. For example, many otherwise smart, well-informed people now confuse “classified” with “accurate.” Starved of truth too long, they have come to accept the same flawed reasoning that brought us Truthers.

The new mainstream assumption, somewhat justified, seems to be that most of what is shared openly by institutional sources, including the news media, consists of lies. Therefore, goes this reasoning, the real story must be hidden somewhere. When the “real story” fails to emerge, skepticism soon gives way to paranoia.

It is wise to doubt the official version of anything. But it does not follow that the hidden story is any more reliable. The problem is epistemological: Secrecy does not denote truth.

Which brings me to Wikileaks. Every time this mysterious organization releases a batch of classified US government files—no matter how obscure or out-of-date—the press covers it like the second coming of John Lennon. Revelation.

No shock there. For most journalists, the publication of secret files ipso facto constitutes a scoop—a scoop so juicy, it may be worth compromising certain principles, such as editorial independence. In the case of the “war logs,” the once-secret files were held under embargo and spoon-fed to select media outlets by Wikileaks, in order to maximize publicity.

Unlike, say, an Apple product launch, the massive attention was warranted. There is some genuinely important news in the war logs. There is also, it must be said, a lot of impenetrable crap.

Although Wikileaks poses as a journalistic organization, the war logs themselves should not be confused with journalism. They fall short on on three levels.

First, the war logs fail as evidence. Merely because Wikileaks and its media partners have confirmed the documents they published are authentic—not forgeries—does not mean that those documents accurately describe events as they happened. (Dan Rather may have had the opposite problem.) The war logs are akin to a police arrest report, which doesn’t tell you the criminal’s version of the story. The missing voices here are Afghan and Iraqi.

Looked at in the most generous possible light, Wikileaks has provided 400,000 starting points for further investigation. That is commendable. But Torture At Abu Ghraib, it ain’t.

Second, the war logs fail as narrative. When it comes to providing a coherent, timely account of the war—half of a journalist’s task—Wikileaks is a bust. Hundreds of thousands of untranslated “SIGACTS” may be of use to historians, investigators and tacticians, but the Wikileaks reports scarcely compensate for a decade’s-long shortage of on-the-scene reporting. What acronym-packed classified memo can say as much about war as a single well-composed photograph from the scene, or an unvarnished first-hand report from a talented writer?

Third, and most importantly, Wikileaks has failed to achieve its stated goal, “to bring important news and information to the public.” The chief reason for this failure is Wikileaks’ own lack of transparency.

Despite Wikileaks’ efforts to draw attention to alleged “war crimes,” the public is hearing a different message—at least in America, where the military remains the most trusted institution, despite countless examples of systematic deception by military leaders. (Pat Tillman? Jessica Lynch? Anyone?)

This comes from a Pew poll conducted after the first wars logs release:

Among those who have heard about the leak, 47% say the disclosure of classified documents about the war in Afghanistan harms the public interest while 42% say it serves the public interest.

Those most attentive to the story take a more critical view of the WikiLeaks release. Among the 37% of the public that has heard a lot about it, most (53%) say the disclosure of classified documents about the Afghanistan war harms the public interest.

Note that people who are paying the closest attention to the war logs release denounce it more quickly than people who are barely following the story. Why might that be?

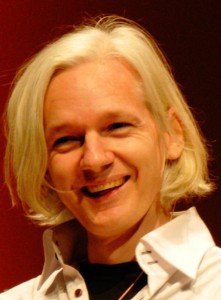

There is an obvious answer. Each new document dump generates more interest in Wikileaks’ problematic public face, Julian Assange, than in the newsworthy contents of the documents themselves.

There is an obvious answer. Each new document dump generates more interest in Wikileaks’ problematic public face, Julian Assange, than in the newsworthy contents of the documents themselves.

The focus on personality over substance is predictable. And in this case, it’s understandable. Assange is an interesting figure, whether you think he’s a cartoon villain or some kind of rock star. Given his ironic obsession with privacy (his own, not others’), who can possibly be sure?

Assange cultivates a mysterious persona, appearing in public with bodyguards, as though Delta Force might drop in through the roof during the middle of a press conference, and whisk him off to Guantanamo Bay. The cloak-and-dagger pose is, in a word, “bogus.” Meanwhile, the leaker who enabled Assange’s fame languishes in actual jail. It’s like the Hollywood story of Capote, but worse.

In reality, Assange is neither villain nor rock star. He is actually a kind of victim—another sucker trapped in the cult of secrecy.

Granted, Assange has an exalted position in this cult, one that inspires awe among the other followers. And he is not an innocent. There is subterfuge at the heart of Wikileaks.

This is the subterfuge:

The people who run Wikileaks must know that any form of electronic communication, originating more or less anywhere in the world, is liable to be intercepted and can, with effort, be traced.

Yet they promise “maximum protection” for the sources of their secrets, sources thanks to Wikileaks’ “high security anonymous drop box fortified by cutting-edge cryptographic information technologies.”

What are these miraculous technologies? Are they proprietary? At least that would explain why their description sounds so much like advertising copy.

As hyperbole is to hucksters, jargon is to liars. What’s the more honest description: Collateralized Debt Obligation? Or “one shitty deal”? Cutting-edge cryptographic information technologies? Or, “Gee, we hope the NSA can’t outwit our crack team of Bay Area hipsters and Russian teenagers.”

There is no reason to trust an organization that cannot or will not explain—in plain terms—exactly how its methods protect the privacy of correspondents. Wikileaks refuses to do so, citing a version of the intelligence agencies’ refrain, “protecting sources and methods.”

This presents potential leakers with an unfair bargain. Deep Throat, at least, knew Bob Woodward’s face—so he knew whose neck to twist off if he ever got burned. Wikileakers should be so lucky.

People who work for a military agency, an intelligence service or a defense contractor may face real, life-and-limb danger if they attempt to reveal the secrets of their employers. The same applies to active dissidents or journalists in any of the countries at the lower end of this list. The consequence of a slip-up could be prison or worse, so would-be whistleblowers must take steps to protect themselves.

This means they have a right to understand why “the anonymous electronic drop box [is] the preferred method of submitting any material” to Wikileaks.

How is the “drop box” preferable to a letter sent through the mail? How can it possibly be preferable to the low-tech methods of communication favored by many successful underground organizations?

Until that’s explained, anonymous sources should save their breath for the parking garage.

As a crash course in the art of surveillance self-defense, Wikileaks’ submissions page doesn’t cut it. (Perhaps that’s why the drop box is “currently closed for re-engineering.”)

Consider what these instructions leave out: Who are the “trusted truth facilitators” so integral to the security of the submission process? Do they include any of the same people who helped Wikileaks get its start by siphoning documents from what was ostensibly a secure, private communications service?

Would-be Wikileakers are advised to pay cash for new electronic storage devices, to avoid creating a financial trail. That’s all well and good. But Wikileaks fails to remind its sources to take the battery out of their cell phones on the way to Office Depot—meaning their movements can still be tracked remotely.

Perhaps the source is already being followed. Fortunately, Wikileaks’ anonymous “journalists” have thought of that one:

If you suspect you are under physical surveillance, discreetly give the letter to a trusted friend or relative to post.

A “trusted” “friend”? Can there be such a thing? Did not Julia betray Winston in Room 101? Or, remind me, was it the other way around?

Do you see where this is going? Where does it all lead, this paranoia?

Constant anxiety short-circuits the brain. Fear smothers the spirit. The cult of secrecy is a dead end.

The worst kind of corruption hides today in plain sight. This website, War Is Business, has set out to highlight that corruption using transparent methods and, as far as possible, open sources.

Anyone can help in that effort. No espionage training required.

Anyone can help in that effort. No espionage training required.

Of course, I’ll take story tips by email. But don’t expect me to protect your identity unless I agree to it first. Trust is a two-way street. Maybe the only thing more irritating than anonymous journalists is anonymous sources.