A bill that passed the US House of Representatives last week could bring to an end the $4.6 billion-a-year military business of KBR, Dick Cheney’s former employer and the 10th-largest US defense contractor.

A bill that passed the US House of Representatives last week could bring to an end the $4.6 billion-a-year military business of KBR, Dick Cheney’s former employer and the 10th-largest US defense contractor.

Last year, KBR admitted guilt in a Foreign Corrupt Practices Act case involving bribes paid to win $6 billion worth of natural gas contracts in Nigeria. The FCPA is the principle US law limiting how much and what kind of graft American companies can pay to foreign officials.

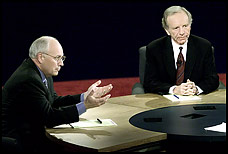

The proposed Overseas Contractor Reform Act would ban government contracts with companies that, like KBR, have violated the FCPA. To become law, the bill must earn the approval of a US Senate committee led by Joe Lieberman, the hawkish Democrat from Connecticut.

Lieberman—pictured with Cheney, above—has accepted at least $615,000 in political contributions from military businesses in his Senate career, so he presumably understands the issues at hand.

Considering that this is the same Congress whose members demanded an apology on behalf of a Biblical-scale polluter, it may seem surprising that the anti-graft bill has so far generated no outrage or opposition from any of the hundreds of lawmakers representing the military-industrial sector.

A closer look at the language of the bill reveals an explanation: The “reform” poses no serious threat to the bottom line of US military contractors engaging in corruption abroad.

KBR, for instance, could keep its military contracting business by requesting and receiving a “waiver” from the Secretary of Defense.

Beyond that Humvee-sized loophole, there is a conceptual problem with the reform bill, having to do with its legal trigger mechanism, the FCPA. Mike Koehler, a business law professor at Butler University, calls the FCPA a “facade” in many cases, and writes that the new reform bill ”may need some tweaking if it is to be effective.”

Reform-minded Senators might look to the UK, which this year passed legislation widely thought to one-up the FCPA. The UK Anti-Bribery Act effect next April, and subjects companies to unlimited criminal liability for a broad scope of business baksheesh.

According to the Financial Times, the new law is making multinationals “nervous.”

Unlike FCPA in the US, the UK’s Bribery Act makes no distinction between petty corruption – such as greasing the palm of a customs officer – and grand corruption such as the pay-off of a government minister.

In its most far-reaching change it sets to prosecute companies not merely for paying bribes but for failing to prevent bribe-paying or receiving among employees.

But this anti-corruption blog says US companies doing business in the UK aren’t too worried about the new law, since they’ve had decades of practice at skirting—er, complying with—such regulations.

Hat tip to Dave Maass for passing along a link to the Overseas Contractor Reform Act.