This man is William B Burdeshaw, a retired US Army Brigadier General and founder of what the Boston Globe, in its must-read investigation of rampant corruption in Pentagon procurement, calls “one of the oldest ‘rent-a-general’ consulting firms” in the country.

This man is William B Burdeshaw, a retired US Army Brigadier General and founder of what the Boston Globe, in its must-read investigation of rampant corruption in Pentagon procurement, calls “one of the oldest ‘rent-a-general’ consulting firms” in the country.

His company, Burdeshaw Associates Ltd, is essentially a fixer for corporations looking to land military contracts. The firm is apparently so good at this, its influential “associates”—mostly retired, high-ranking officers—can sell the Pentagon things it didn’t even know it needed.

Read Globe reporter Bryan Bender describe how Burdeshaw cleverly wrung $109 million from the Pentagon for the firm’s client, Northrop Grumman, which wanted to build a remote-controlled helicopter called the Fire Scout.

To get the Fire Scout off the ground, Burdeshaw did more than just set up meetings with key Army decision makers. It was hired by Northrop Grumman to write a “concept of operations’’ for the aircraft…an official document that is a crucial step in defense procurement.

The takeaway is, before Northrop hired Burdeshaw, the military saw no need for an unmanned surveillance helicopter.

After the Army adopted the concept, it gave Northrop a 10-year deal and paid the firm $109 million to build eight Fire Scouts. But they are still sitting at Northrop Grumman’s Mississippi plant, unused. With little explanation, the service decided earlier this year that it didn’t need the aircraft after all.

The Army wouldn’t comment. Northrop Grumman wouldn’t comment. Burdeshaw’s chief executive, retired Army General William Hartzog, wouldn’t comment. Bender did a remarkable job of putting this story together despite such obstacles.

Clearly, no one gained from this episode—except Northrop Grumman, the third-largest US military contractor, and Burdeshaw Associates. The firm’s eponym seems to be doing well for himself. Burdeshaw and his wife, Monica, own a massive $2 million home near the Potomac River in Maryland. Give the size of his firm, his personal wealth is likely many times that amount.

Here is what the Globe has to say about how much money a retired general or admiral can earn by trading on his access, authority and presumed integrity:

For the rapidly growing corps of [retired military] consultants, fees reach thousands of dollars a day; monthly retainers can run between $20,000 and $50,000 for individual clients. The busiest and most influential retired generals are earning millions of dollars a year, according to industry sources.

Even with a generous pension — 100 percent of their salary and lifelong benefits — a number of retired generals interviewed by the Globe said they needed to make more money after decades of living on a military salary and saving little.

Well, then—aren’t they the real victims, here?[visitor]

HELP RESEARCH MILITARY CONTRACTORS. ACCESS MORE OF THIS SITE. BANISH THESE BANNERS.

[/visitor]

The Globe leads its investigation by quantifying the evolution of the rent-a-general business: In the mid-90s, fewer than half of the three- and four-star officers who retired from military service became consultants or defense industry executives. In 2007, a full 90 percent did.

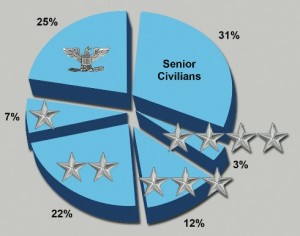

There’s plenty of work for lower-ranking officers and civilians, as well. As this chart shows, only 15 percent of Burdeshaw’s associates are three- and four-star officers. (The firm also has a number of ambassadors, intelligence agents and foreign military officers on its payroll.)

There’s plenty of work for lower-ranking officers and civilians, as well. As this chart shows, only 15 percent of Burdeshaw’s associates are three- and four-star officers. (The firm also has a number of ambassadors, intelligence agents and foreign military officers on its payroll.)

Many of those “retired” military consultants retain important advisory roles within the Pentagon, a clear conflict of interest that goes ignored by the military. And rent-a-generals are often recruited by the private sector long before they retire—another potential conflict, and one that the military actively encourages.

“When a general-turned-businessman arrives at the Pentagon, he is often treated with extraordinary deference — as if still in uniform,” the Globe says. This “can greatly increase his effectiveness as a rainmaker for industry.” In return for selling their old colleagues and subordinates on new and quite often unnecessary weapons systems, some rent-a-generals are even rewarded with equity stakes in the companies they de facto represent.

The whole article in the Globe is well worth your time. In its conclusion, Bender explains the growing demand for rent-a-generals as a consequence of “the increasing importance of the military to America’s industrial base.” Retired Army General and former Presidential candidate Wesley Clark calls it “the militarization of the economy.”

Too see what the militarization of the economy looks like, visit a discount grocer in any American city and count how many people pay with food stamps. Then ponder William Burdeshaw’s mansion.

Too see the effects of a simultaneous process—the commodification of the military—look no farther than Afghanistan, where contractors outnumber uniformed soldiers.