![]() The man on the left works for the Defence Industries Corporation of Nigeria, a government-owned arms manufacturer.

The man on the left works for the Defence Industries Corporation of Nigeria, a government-owned arms manufacturer.

The man on the right works for DICON’s “Chinese technical partners”— possibly Poly Technologies, Inc., the China Poly Group spinoff that struck a weapons production deal with Nigeria in 2004.

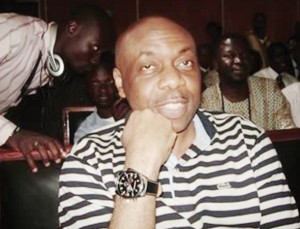

The third man, pictured below, is Henry Okah, who is now on trial for acts of terrorism against the government and oil companies in Nigeria.

Guess which country is selling him weapons?

Okah led a guerilla group that staged attacks on oil rigs in the Niger Delta, primarily those owned by Shell. Before his latest arrest, he had accepted an amnesty offer and was living in South Africa, where he is now on trial.

Okah led a guerilla group that staged attacks on oil rigs in the Niger Delta, primarily those owned by Shell. Before his latest arrest, he had accepted an amnesty offer and was living in South Africa, where he is now on trial.

Prosecutors said they also found in Okah’s home a Sept. 3 invoice from a Chinese company not registered to deal in arms in South Africa showing the price of rocket launchers, rocket-propelled grenades, hand grenades, guns and heavy artillery.

I can’t find a press account that names the Chinese company that was selling to Okah; the reporting also doesn’t say which governments had failed to license the Chinese company.

Those missing facts leave open the question of whether the arms sale to Okah was in any way sanctioned by the Chinese government, which is supposed to monitor and approve all arms exports.

If that were the case, it would suggest China is arming two sides of an ongoing conflict in Africa—one which involves competing foreign oil interests and a government threatened by multiple rebel groups.

But if—as seems more likely—the Okah deal was purely a black-market transaction, it’s another milestone in China’s long economic transition. What says lassiez-faire like the unregulated export of heavy artillery?